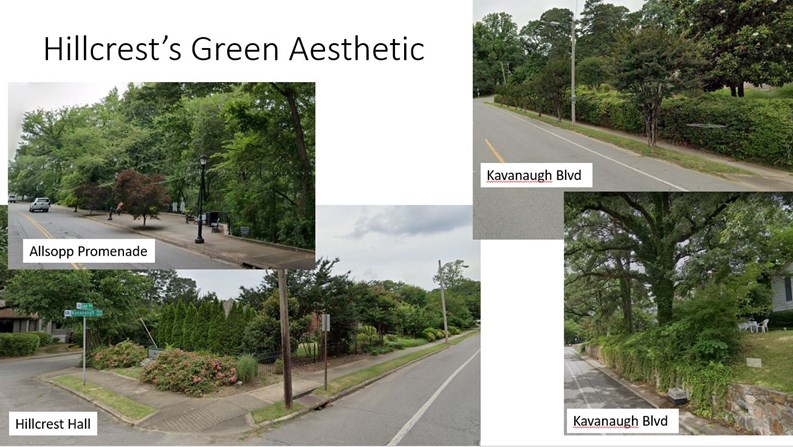

Kavanaugh Aesthetics

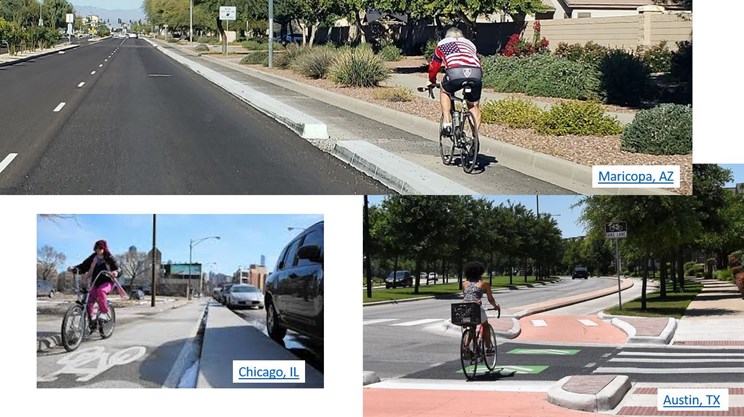

A one-size-fits-all approach does not work well with building a bike network. While it is important to create suitably protective facilities (Fig. 1), it’s also important to consider street and neighborhood context. One thing the City has heard loud and clear from the Hillcrest Residents Association (HRA) is that, in Hillcrest, aesthetics matter (Comments 21-22). The City has been working with the HRA to find a design that is suitably protective and fits the HRA’s aesthetic. The City has considered how every possible physical separation discussed in FHWA’s Separated Bike Lane Planning and Design Guide could be applied to Kavanaugh. If the City can get a short-list of the best-fit facility types for the HRA’s aesthetic, we could explore in greater depth what those could look like on Kavanaugh.

Funding

The least expensive options are parking stops and delineators, just parking stops, or just delineators. The City currently has funds to install any of these three options thanks to generous funding from People for Bikes. The HRA has indicated that these choices do not reflect the HRA’s aesthetic. The City does not currently have funding to create other types of facilities that may better match the HRA’s aesthetic. One possible path forward would be for the HRA to choose the least offensive option from among the three immediate possibilities now with an eye to installing the HRA’s preferred facility type in the near future. To be clear, City staff and elected officials have not yet approved these designs nor have they approved seeking grant funding to construct these designs. This page is simply meant to show all stakeholders the full menu of design possibilities for Kavanaugh so that we can determine if there is a choice that all stakeholders could rally behind. If that option does exist, it may change how best to set up the bike facility now.

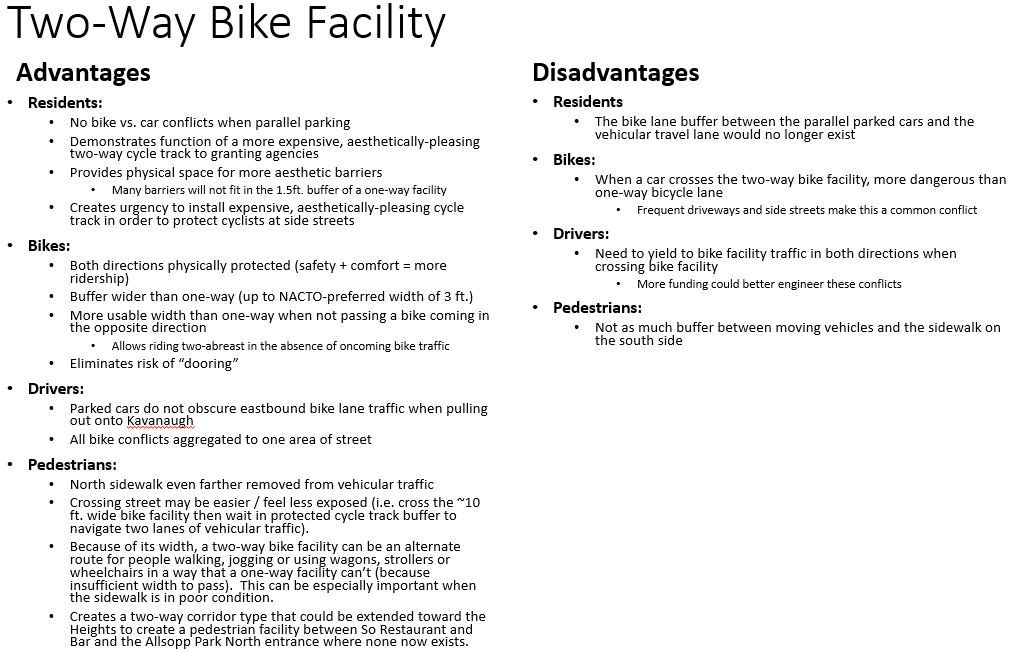

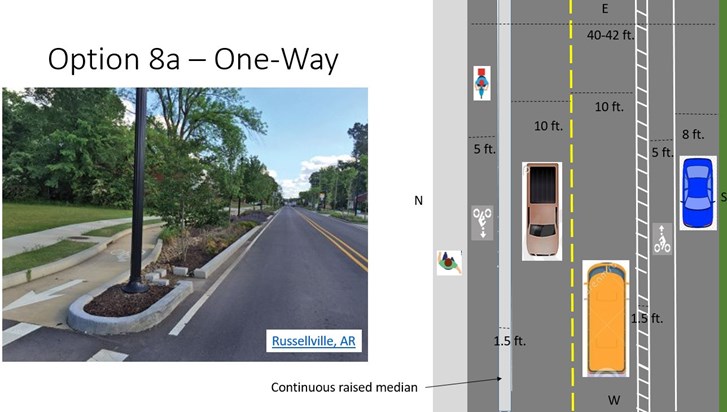

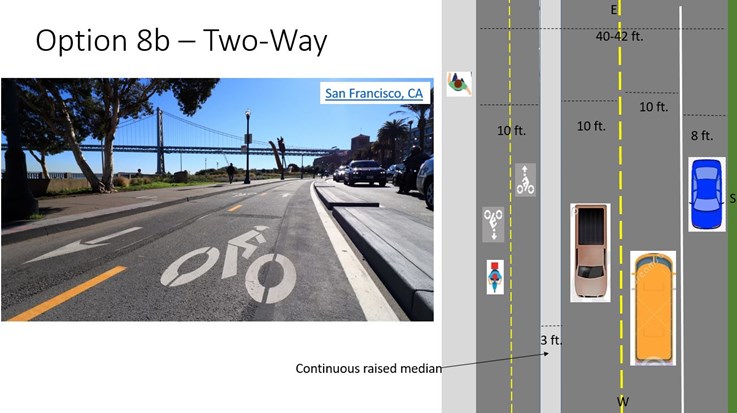

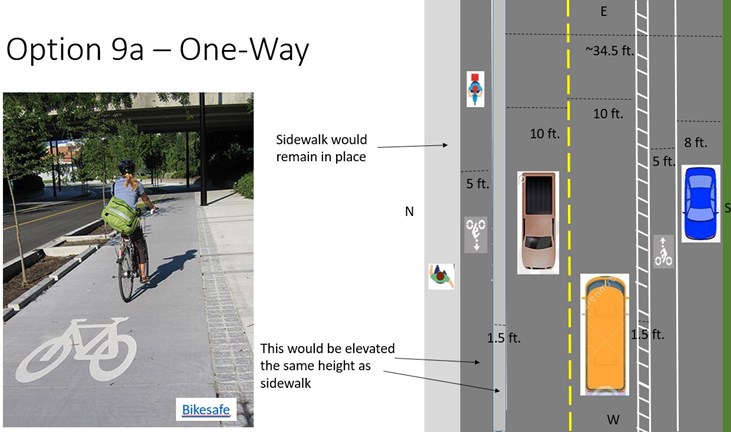

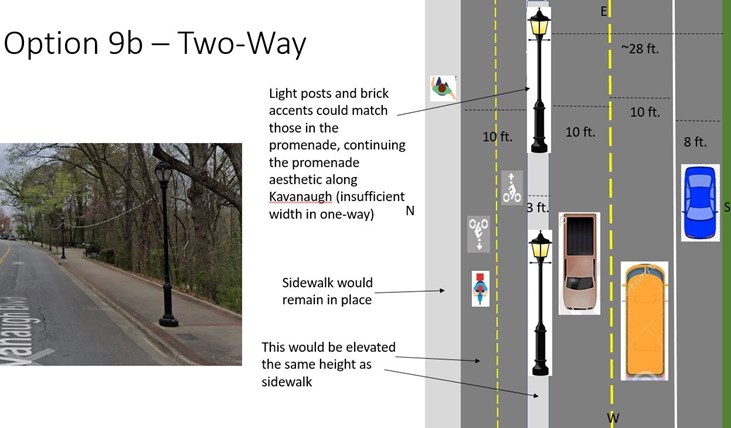

One-Way vs. Two-Way Bicycle Facility

One-way bike lanes on Kavanaugh make sense if the ultimate goal were to install them for the long-term with one of the three options funded by People for Bikes (i.e. when the method of physical protection is relatively inexpensive). They allow bicycle traffic to move in the same direction as vehicular traffic, making traffic patterns more intuitive for people biking and people driving and they protect riders as they are going uphill with the greatest difference in speed between car and bike (e.g. Fig. 2). However, if the HRA’s optimal aesthetic requires a much more expensive bike facility, then this traffic pattern becomes more difficult to justify and to secure grant funding to construct. It would be a tough sell to tell a granting agency that we intend to spend tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars to protect people riding in one direction, but people riding in the other direction will continue to be sandwiched between parallel parking and a traffic lane with no physical protection and a risk of “dooring” (e.g. Table 1). That’s not a good use of grant agency funds and likely would not get funded. In addition, if the City secured grant funding to build a more expensive bicycle facility, we would have the funds to make intersections between the bike facility and side streets safer (the main drawback to a two-way facility, see also Table 1 and Question #5).

Why consider this now? It may be best to consider a phased approach, installing one of the three options for which we have funds that must be used now and then seek funding to construct the HRA’s preferred option in an upcoming grant cycle. Funds for the HRA’s preferred facility would actually be much easier to secure if we followed this phased approach, because the granting agency would see that the proposed traffic pattern works, it is safe, feels safe for all users, and the City has community buy-in (like a pop up does). But we would only have these benefits if the traffic pattern of Phase One approximated the traffic pattern we intend to create in the grant. It would also further incentivize the City to secure funding for this optimally aesthetic facility in the near future in order to make crossings of the two-way facility safer. In short, City staff recommends inexpensive one-way bike lanes, BUT if the HRA wants to create a more expensive bicycle facility on Kavanaugh for aesthetic purposes, it may be best to start with a two-way cycle track on the north side of Kavanaugh.

Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages of installing a two-way cycle track vs. City-proposed one-way facilities on Kavanaugh.

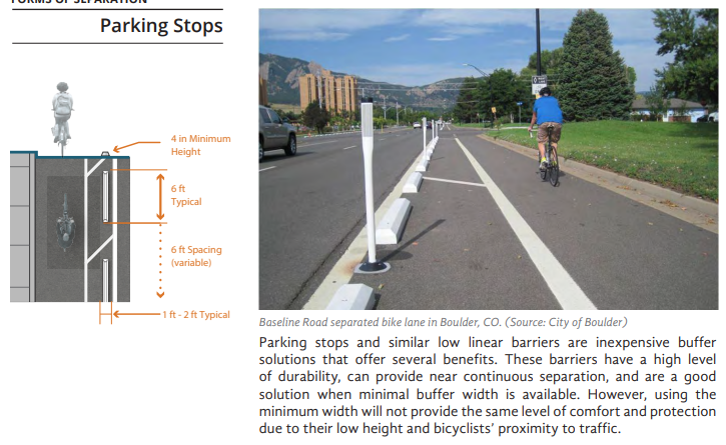

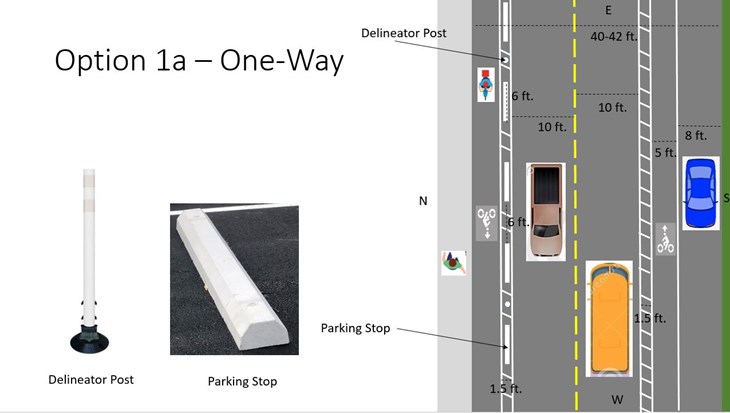

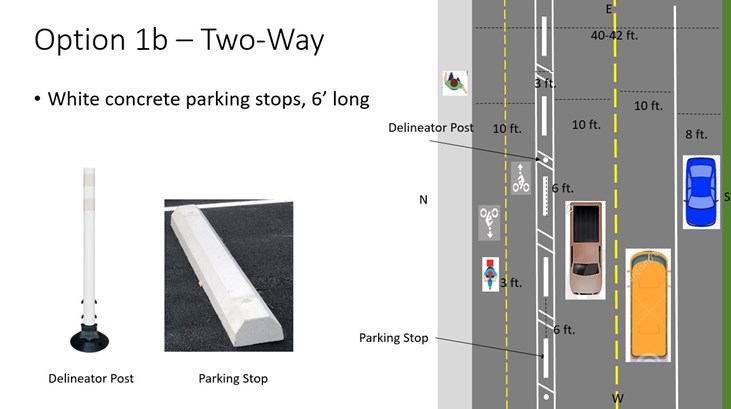

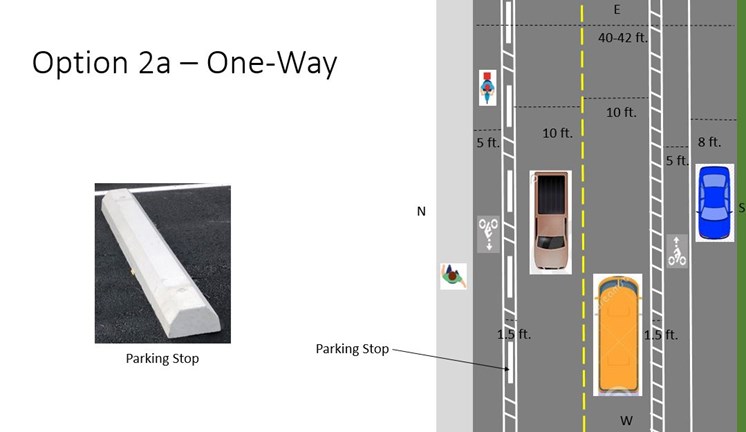

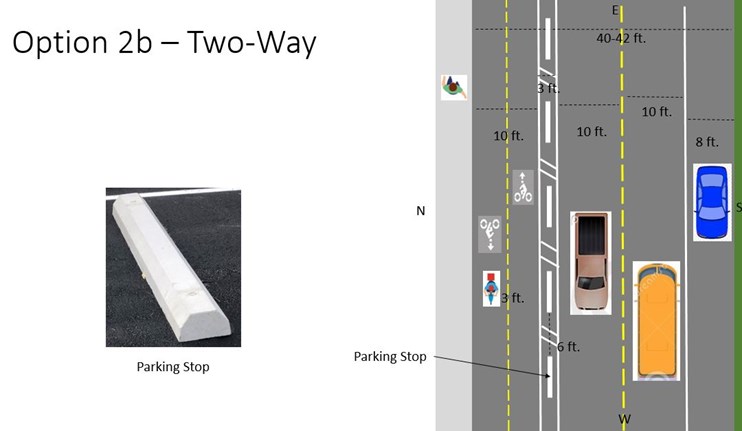

Parking Stops and Delineators

This is the option originally proposed by the City. The parking stops provide a reasonable physical separation between cars and bikes and the flexible delineators provide a vertical element, both clarifying to drivers that their is a physical obstruction in the roadway and creating a more comfortable separated space for cyclists (Figs. 1-5). We have the necessary funding to install this now.

Figure 1. Description of a parking stop and delineator physical protection from FHWA.

Figure 2. Aerial concept of a one-way facility with posts and stops.

Figure 3. Aerial concept of a two-way facility with posts and stops.

Figure 4. Example of a bicycle lane protected by stops and delineators. As proposed, the one-way facility itself would look a lot like this.

Figure 5. Example of a bicycle lane protected by stops and delineators in a historic residential neighborhood.

Parking Stops Only

This is the option originally proposed by the City but without the delineators (Figs. 6-8). While the parking stops would provide a reasonable physical separation between cars and bikes, there is little in the way of a vertical element. This would make people on bikes feel more exposed and would make the physical obstruction in the roadway less obvious to people driving, perhaps increasing the risk of a car vs. parking stop collision and car encroachment into the bike lane. We have the necessary funding to install this now.

Figure 6. Aerial concept of a one-way facility with stops only.

Figure 7. Aerial concept of a two-way cycle track with stops only.

Figure 8. Example of a two-way cycle track protected by parking stops only.

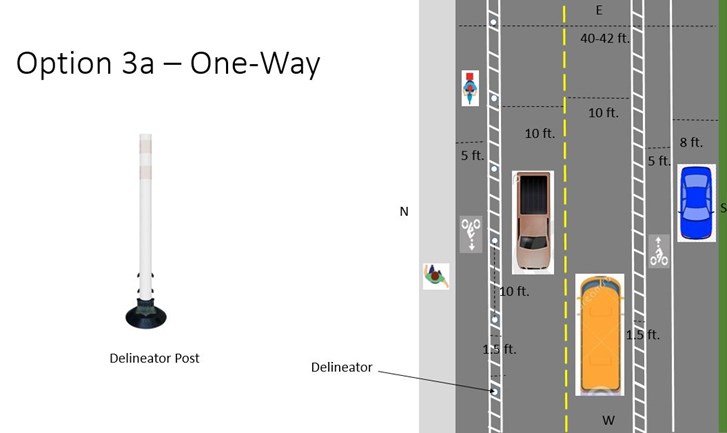

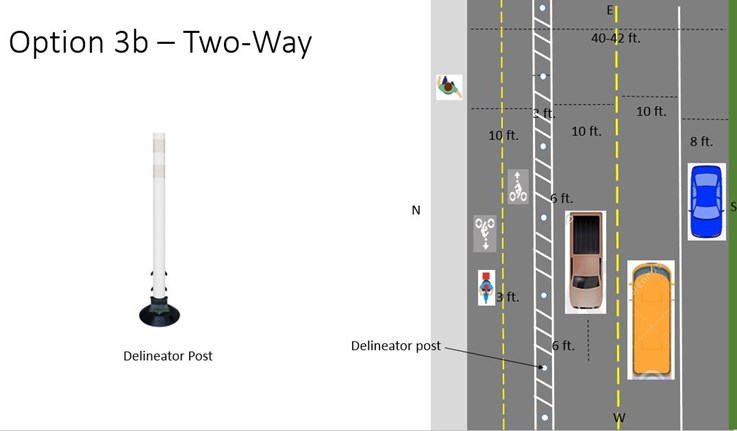

Delineators Only

This is the similar to the option originally proposed by the City, but without the parking stops (Figs. 9-13). While the delineators would provide a vertical element and a visual separation between cars and bikes, these flex posts do not physically protect someone on a bike from a car entering the bike lane. This facility type is very common, perhaps the most common “protected” bike lane, not because it is particularly protective, but because it is inexpensive and checks the box of a protected bike lane. We have the necessary funding to install this now.

Figure 9. FHWA description of a bike lane protected by delineator posts.

Figure 10. Aerial concept of a one-way bike lane on Kavanaugh protected by delineators only.

Figure 11. Aerial concept of a two-way bike lane on Kavanaugh protected by delineators only.

Figure 12. Example of a one-way delineator-protected bike lane in a historic neighborhood.

Figure 13. Example of a two-way delineator-protected bike lane in a historic neighborhood.

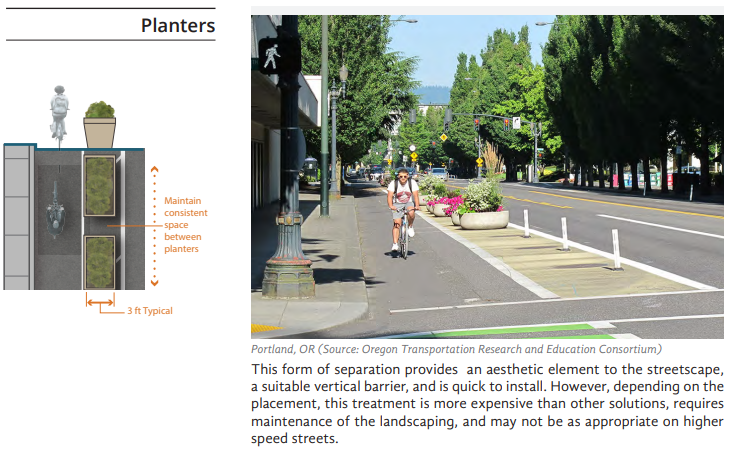

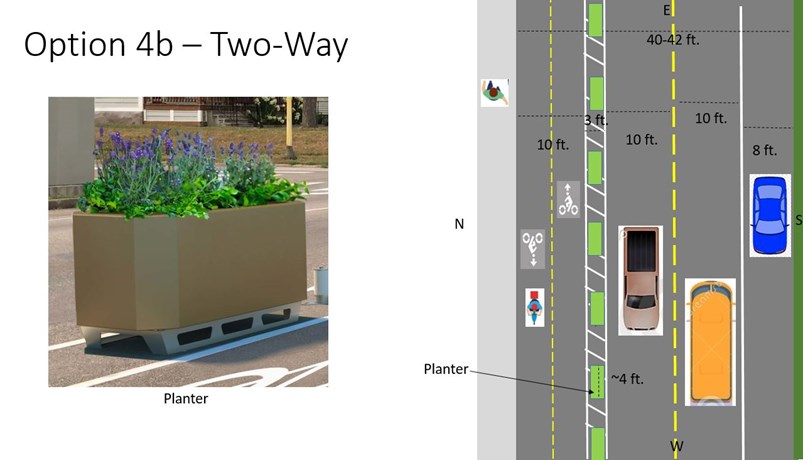

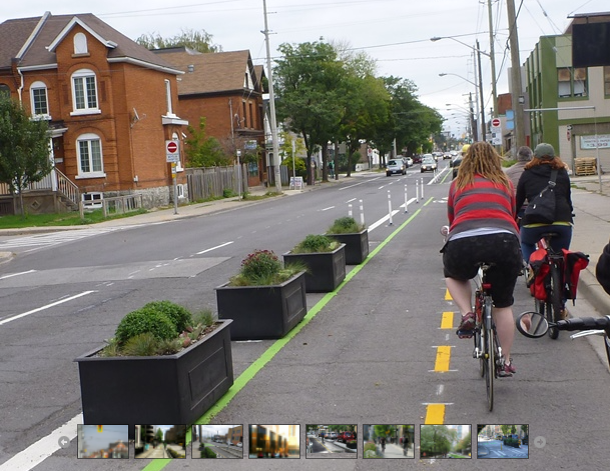

Planters

Please note that the three options above are funded. The “Planters” option, and all options to follow, are not currently funded (Figs. 14-20). These are discussed here to show the HRA and other stakeholders the full range of possibilities on Kavanaugh. When we have a consensus of what we are ultimately trying to achieve on Kavanaugh, we can make decisions that will lead us to that outcome.

Planters can be a beautiful and effective option to separate car and bicycle traffic. They might be a particularly good fit for Kavanaugh, which already has a green aesthetic. However, planters are expensive to construct and time-consuming to maintain. If not properly maintained, they can become an eyesore. For this reason, the HRA would be well-advised to have a maintenance plan for this type of facility before it is constructed. Combining the aesthetics of planters with the low-maintenance needs of stops and/or delineators might be a good compromise.

Figure 14. FHWA presentation of planters as a physical protection of a bike lane.

Figure 15. Photos illustrating Hillcrest’s green aesthetic.

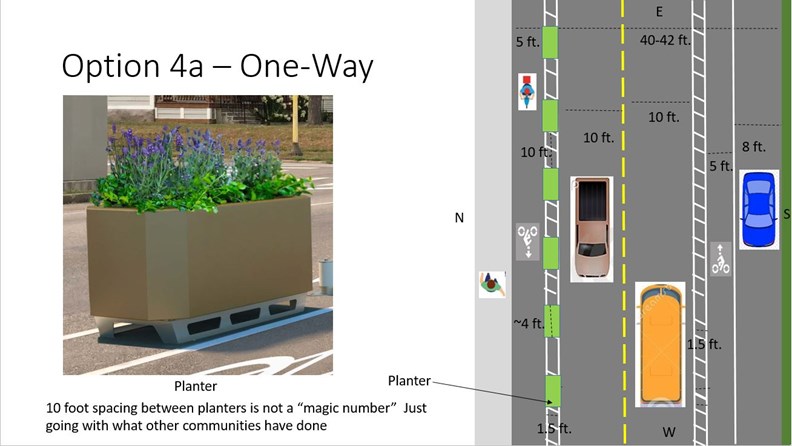

Figure 16. Aerial concept of a one-way bike lane protected by planters.

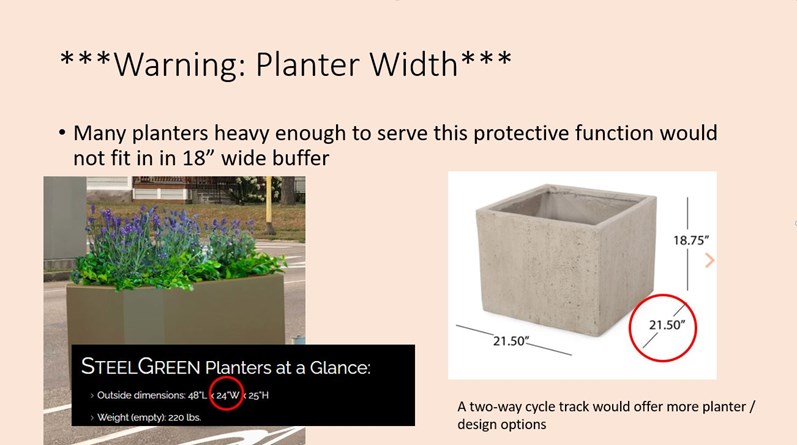

Figure 17. Planters heavy enough to serve a protective function will often be wider than 18 inches (the width of the buffer in a one-way protected bike lane on Kavanaugh).

Figure 18. Aerial concept of a two-way cycle track protected by planters.

Figure 19. Example of a two-way cycle track protected by planters (and stops) in a historic neighborhood.

Figure 20. Given the effort required to maintain the planters, a similar aesthetic might be achieved by having some planters in combination with another protective element (e.g. delineators or stops).

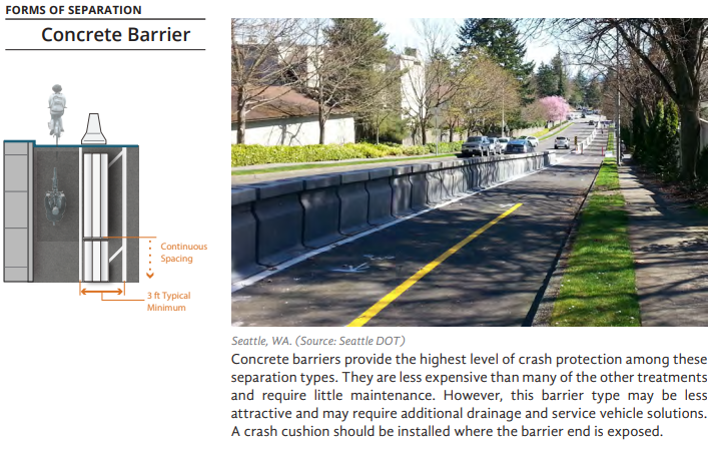

Concrete Barrier

A concrete barrier may be the most protective barrier, but many do not like their aesthetics (Figs. 21-23). It also makes merging into the travel lane to make a left turn difficult for a someone in the cycle track. Still, creative paint or design could make these a possibility for Hillcrest. As noted in the FHWA description, these would only be possible (spatially) with a two-way cycle track.

Figure 21. Concrete walls provide strong protection.

Figure 22. A concrete wall can be a canvas onto which a neighborhood puts its stamp. A timeline of the Hillcrest neighborhood in graphic form might be desirable.

Figure 23. A suitably protected two-way cycle track (or sidepath) can be an alternative route for someone jogging or on a mobility device (especially important when the sidewalk is in disrepair) in a way that a one-way bike lane cannot (insufficient room to pass).

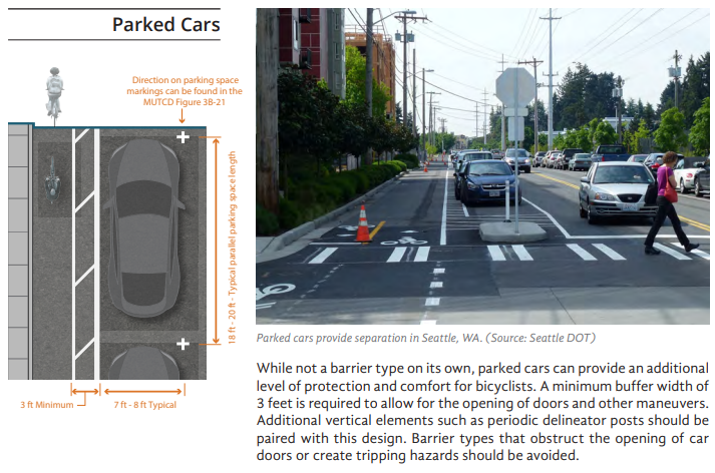

Parking Protected

Parallel parked cars can be an effective barrier between a vehicular lane and a bike lane, but they can have significant trade-offs (Fig. 24). Parkers can sometimes be confused about how to use the facility and end up parking in the bike lane (against the curb). We sometimes see that in Little Rock’s only protected bike on Louisiana between 4th and 10th Streets. Also, it can be difficult for people driving and people biking to see and account for one another (because of the height of the parked cars). This is a safety disincentive. To account for this visibility issue, parking has to be restricted around side streets and driveways. There are so many side streets and driveways that parallel parking capacity would decrease below demand for some Kavanaugh blocks with this facility type. For these reasons, it is not likely in the neighborhood’s or the City’s best interests to attempt this facility type on Kavanaugh.

Figure 24. Parking protection would not likely be good fit for Kavanaugh.

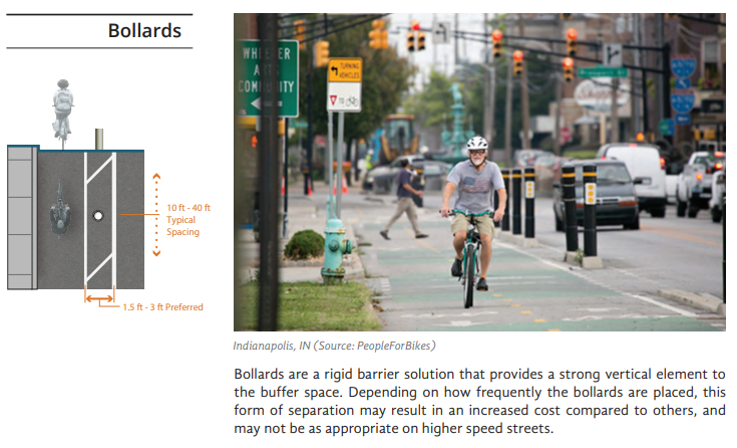

Rigid Linear Bollards

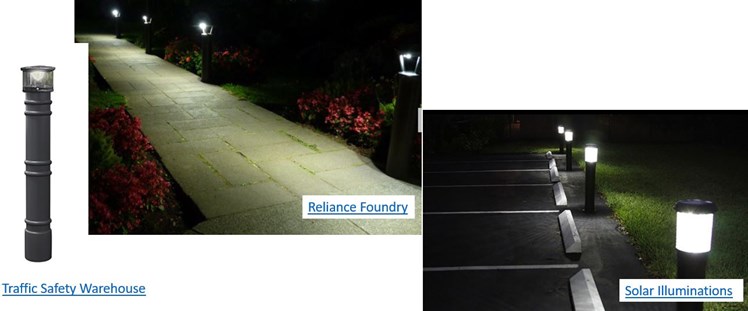

The HRA was clear about not liking the aesthetics of delineators. Rigid bollards are different than delineators; their aesthetic appeal to the HRA may or may not be different from delineators (Figs. 25-31). Like delineators, linear bollards are shaped like posts. Like delineators, they don’t have a wide footprint in the roadway and would be a good fit (spatially) in the 1.5 ft. buffer of a one-way bike lane on Kavanaugh. Unlike delineators, bollards are rigid and would provide an element of physical protection for the bicycle lane (while also providing that important vertical element). Linear bollards can be fitted with decorative bollard covers. Some of these bollard covers can be lit with a light that is charged with a solar panel during the day. Bollards are expensive, so getting a one-way bike lane with bollards funded by a granting agency while the other direction of bicycle traffic is not protected at all may be a challenge (see also “One-Way vs. Two-Way Bicycle Facility” above).

Figure 25. FHWA’s description of bollards as a physical protection for a bicycle facility.

Figure 26. Aerial concept of a one-way bicycle lane protected by linear bollards.

Figure 27. Aerial concept of a two-way bicycle lane protected by linear bollards.

Figure 28. Different examples of linear bollard covers.

Figure 29. More examples of linear bollard covers.

Figure 30. Still more examples of linear bollard covers.

Figure 31. Some linear bollard covers have solar-powered lighting.

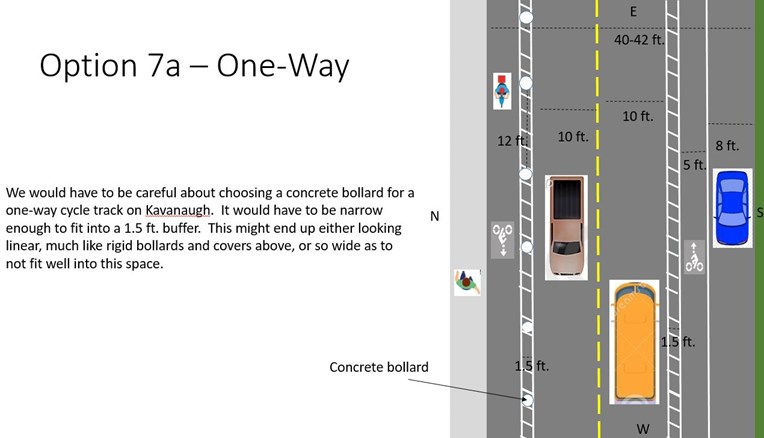

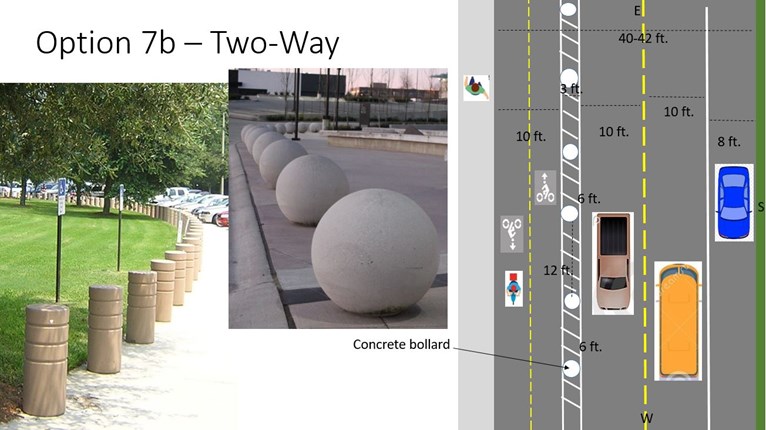

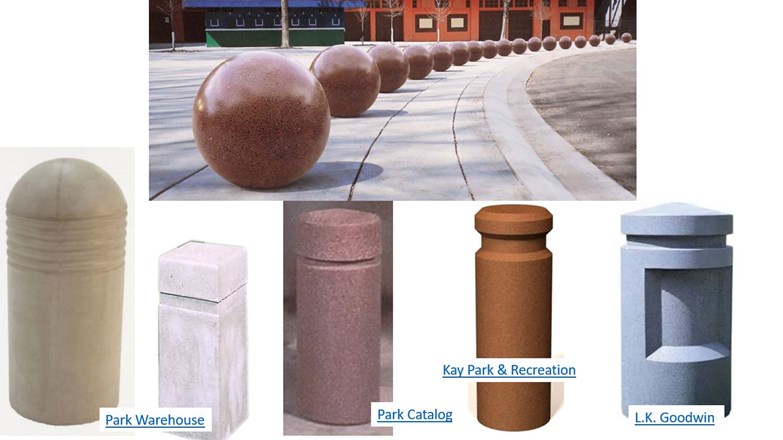

Concrete Bollards

Concrete bollards have a lot of the same properties as rigid linear bollards: they provide a physical barrier to a car entering the bike lane, they have a vertical element, and they are much more expensive than parking stops and/or delineators (Figs. 32-34). Some concrete bollards are shaped like posts, but are typically wider than rigid linear bollards. Some concrete bollards have other shapes, like spheres, and have an even wider profile. For these reasons, concrete bollards would not be a good fit for the 1.5 ft. buffer of a one-way cycle track spatially.

Figure 32. Aerial concept of a one-way bike lane protected by concrete bollards.

Figure 33. Aerial concept of a two-way cycle track protected by concrete bollards.

Figure 34. Examples of concrete bollards.

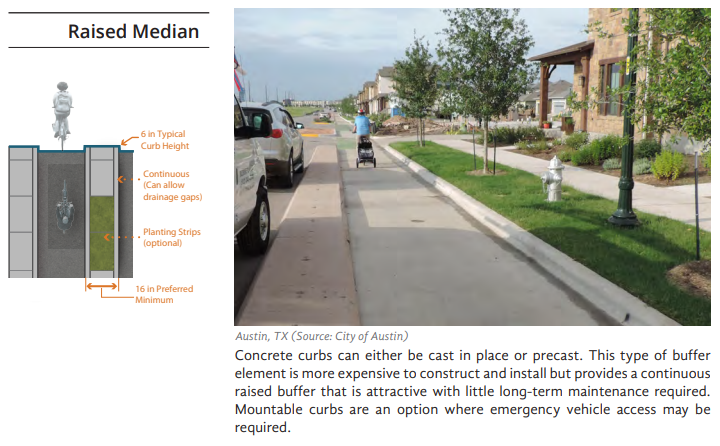

Raised Median

This keeps the cycle track at the same height as the roadway but installs a raised median, typically about the height of a curb, in between the vehicular lane and the cycle track (Figs. 35-38). The raised median could be modular concrete barriers or could be curb and gutter with or without grass or shrubbery in the median. Like the rigid linear bollards, this could fit in an 18-inch buffer spatially but may not make sense strategically when seeking funds from granting agencies.

Figure 35. FHWA’s description of a raised median as a physical barrier for a cycle track.

Figure 36. Aerial concept of a one-way bike lane protected by a raised median.

Figure 37. Aerial concept of a two-way bike lane protected by a raised median.

Figure 38. Examples of one-way cycle tracks protected by raised medians.

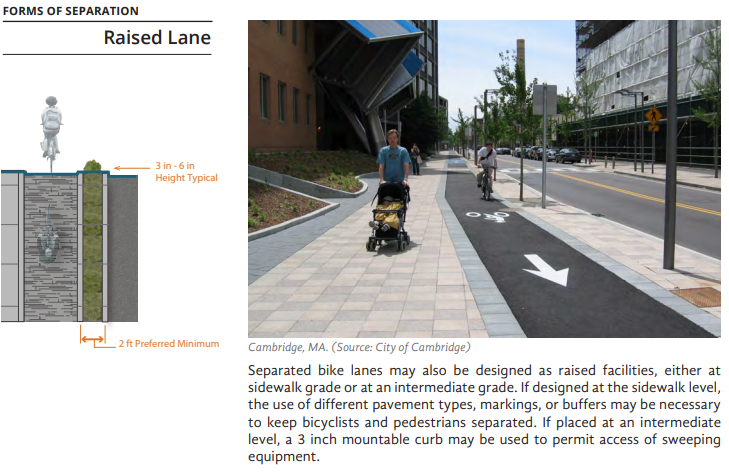

Raised Lane

This is similar to a raised median, but the cycle track is not at the same height as the roadway. The facility would probably be a poor fit for a one-way cycle track on Kavanaugh (buffer is not as wide as FHWA minimum recommended width and does not protect person on bike going in the other direction).

Figure 39. FHWA description of a cycle track protected by a raised lane.

Figure 40. Aerial concept of a one-way cycle track protected by a raised lane.

Figure 41. Aerial concept of a two-way cycle track protected by a raised lane.

Figure 42. Examples of a cycle track protected by a raised lane.

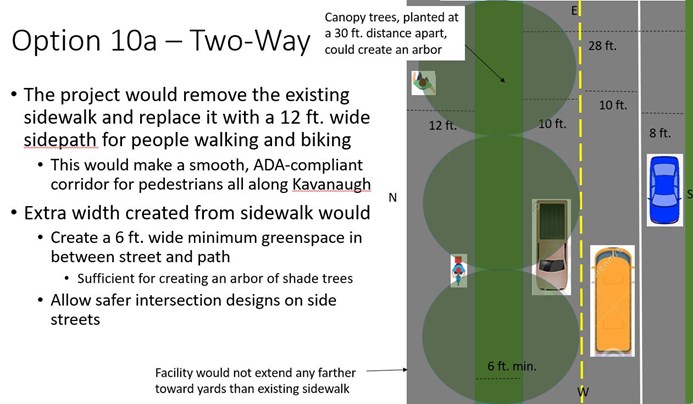

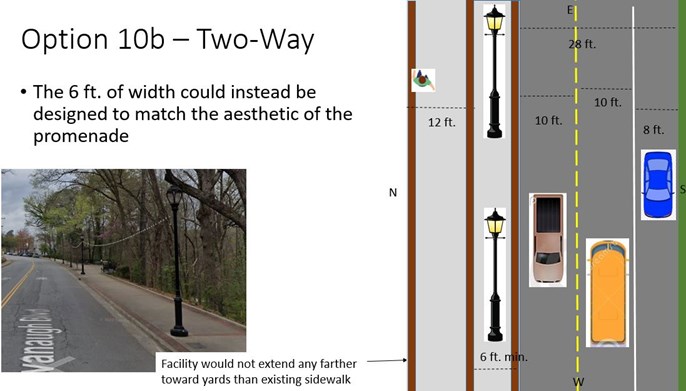

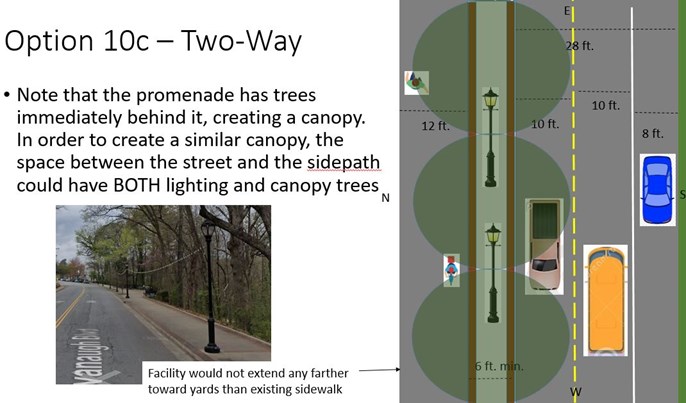

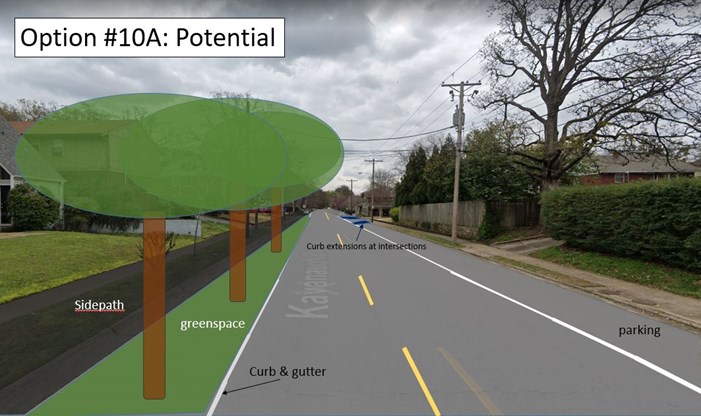

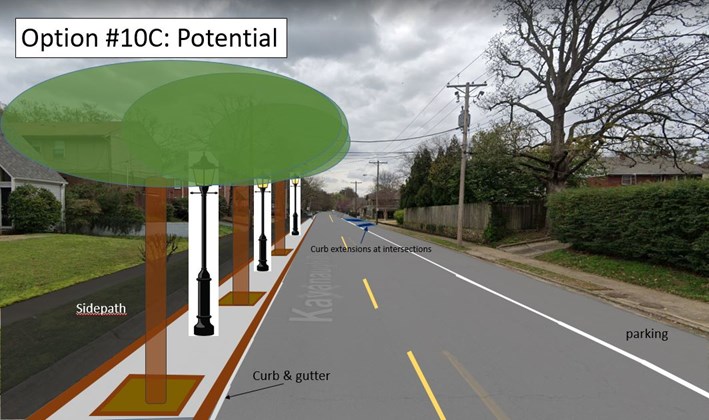

Sidepath

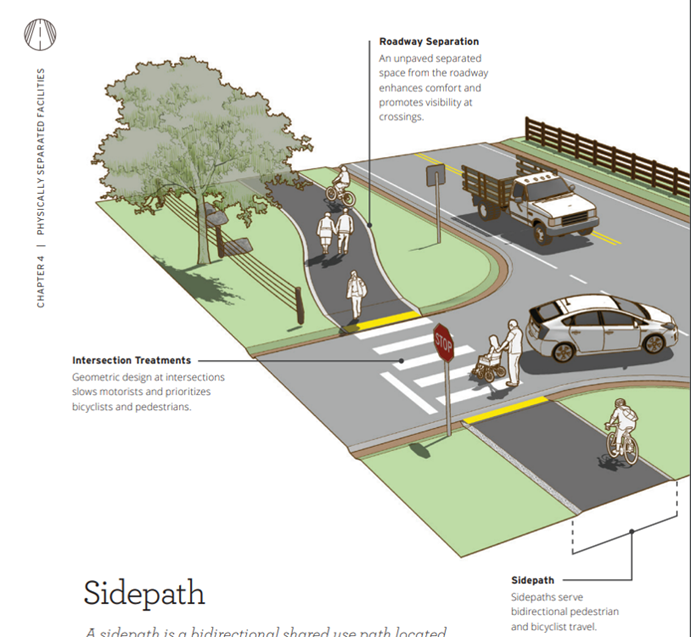

Technically, a sidepath is no longer a bike lane. It’s a shared-use path for people walking and biking, but one that travels along a roadway. The advantage of this facility over a raised median or raised lane is that we could go beyond the existing curb and claim the area currently used by the sidewalk. This would create a brand new pedestrian facility as well, in good repair for strollers, wagons, and wheelchairs, and also create additional width that could be used for aesthetic landscaping without going any further away from the roadway than the existing sidewalk.

Figure 43. FHWA description of a sidepath (Small Town and Rural Multimodal Design Guide).

Figure 44. Creating a sidepath would provide the necessary width between the street and the path to create a continuous tree arbor. Not only would this be an aesthetic asset to the neighborhood, it would provide shade to the sidepath, making it more comfortable and used 12 months out of the year. ***A sidepath is a bicycle AND PEDESTRIAN facility***

Figure 45. Instead of a tree arbor, the neighborhood could continue the Allsopp Promenade aesthetic along the entirety of Kavanaugh, extending the park into the neighborhood. ***A sidepath is a bicycle AND PEDESTRIAN facility***

Figure 46. Even though Option 10b above might look most like the promenade, notice how the tree canopy from Allsopp Park frames the promenade. This continuous tree canopy wouldn’t be extended along Kavanaugh from front lawns. Option 10c might serve maintaining this arbor aesthetic best. ***A sidepath is a bicycle AND PEDESTRIAN facility***

Figure 47. This is how Kavanaugh looks now.

Figure 48. This is how Kavanaugh could look with a sidepath and a continuous tree arbor.

Figure 49. This is how Kavanaugh could look with a sidepath and street lighting.

Figure 50. This is how Kavanaugh could look with a sidepath and street lighting.

Figure 51. It turns out the folks at McClelland Engineering are much better at graphic design than I am. This gives you a better idea of what Kavanaugh could look like with a sidepath and curb extensions. Note that the sidepath’s depicted dashed yellow line is fine but is not necessary, the sidepath could be made of asphalt (depicted) or concrete to better match the promenade, and could be raised to curb height (more like a “raised lane”) vs. what is depicted (more like a “raised median”).

So, what do you think? Do you like anything you see? Let us know!