12th Street Road Diet

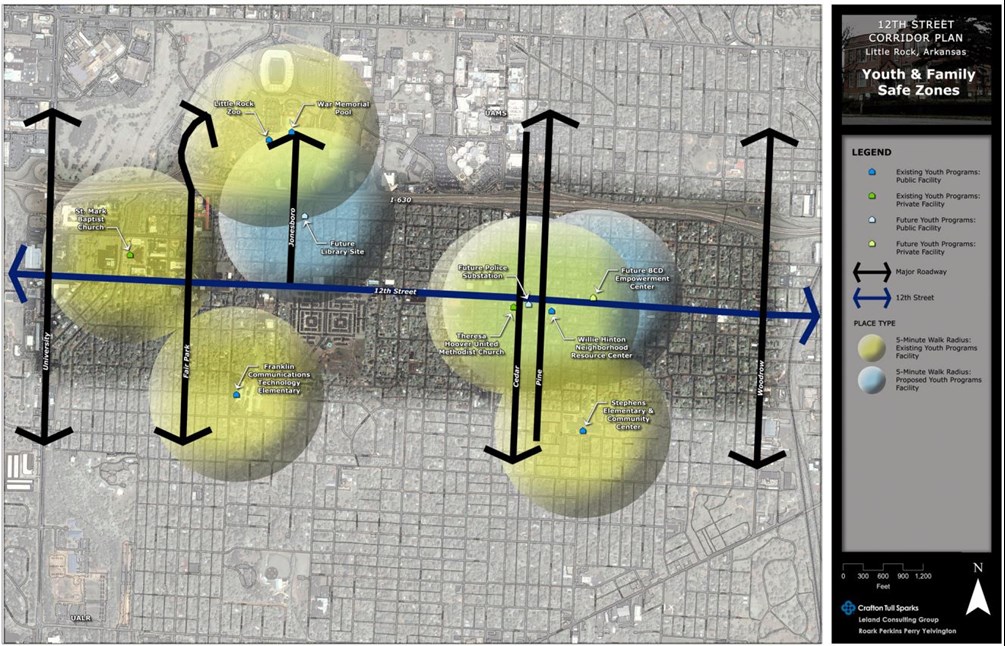

The 12th Street road diet from Jonesboro to Wolfe St. was completed to serve the current safety and transportation needs of local neighborhoods of the 12th St. Corridor (Corridor), assist Corridor revitalization, and provide regional bike connectivity (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. This figure defines Corridor boundaries. Revitalization efforts focus on walkability to youth destinations.

Local Importance

Road diets can improve safety, calm traffic, and make streets more accommodating for all modes of transportation (walking, driving, biking, transit, and emergency vehicles), which is why US DOT/FHWA is encouraging their implementation, especially on four lane roads meeting certain criteria. Road diets increase pedestrian comfort by increasing the distance between sidewalks and moving cars and make roads safer to cross by decreasing the number or vehicular travel lanes and create a dedicated space for bicycles (Figs. 2 & 3). While study after study confirms the safety benefits of road diets for all road users, Figures 2 and 3 can also be illustrative. Which street would you rather cross on foot? On which street would you rather ride a bicycle? On which street does it look like you should drive faster/more aggressively? Along which street would you rather let your children play?

Figure 2. This is how W. 12th Street looked in July 2007.

Figure 3. This is the same location as Fig. 2 in September 2016.

Road Diet Serves the Corridor As It Exist Now

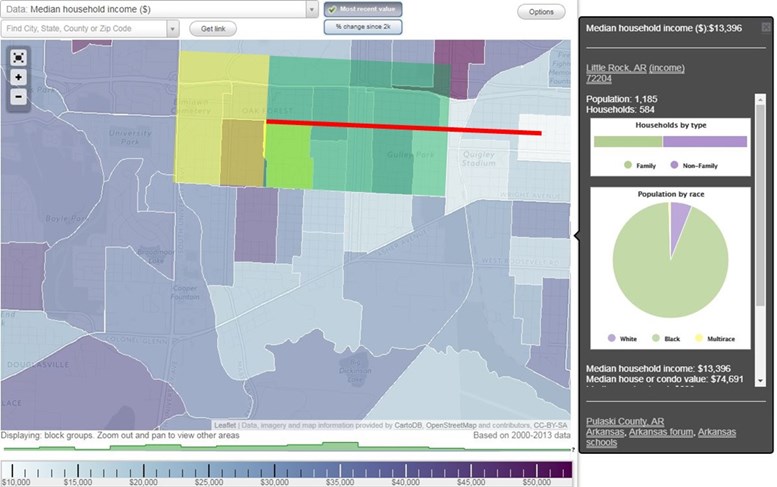

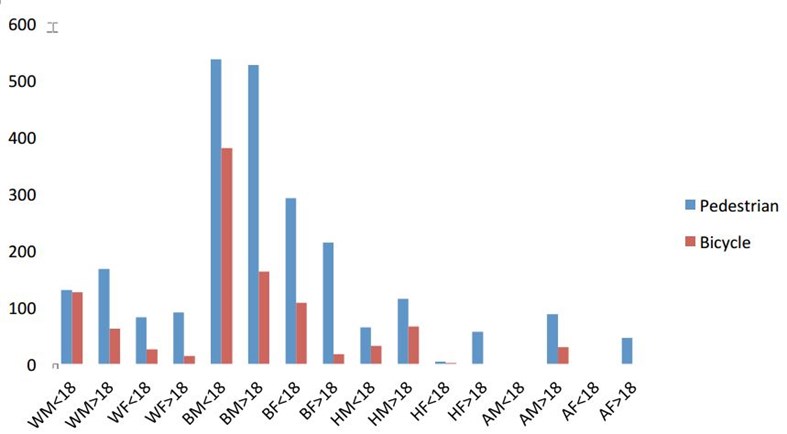

Many of the households who live within the Corridor are African American and have low incomes (Fig. 4). African Americans are three times more likely to be hit by a car than when riding a bike and 3.3 times more likely to be hit by a car when walking than whites in Central Arkansas (Fig. 5). The reasons for this dramatic disparity are likely complex, but one reason may be that bike and pedestrian facilities are more often located in high-income, predominantly white communities than in low-income communities, predominantly African-American communities. The 12th St. road diet was an opportunity to increase the equity of bike and pedestrian accommodations in Little Rock.

Figure 4. The Corridor where the road diet (red line) was implemented (green box) and where it wasn’t implemented (yellow box) superimposed on a demographic map of race and income. Map from city-data.com.

Figure 5. The number of pedestrian and bicycle crashes per 100,000 residents of each demographic in the Little Rock metro area from 2004-2013 (WM=white male, WF=white female, BM=black male, BF=black female, HM=Hispanic male, HF=Hispanic female, AM=Asian male, AF=Asian female). From Metroplan’s Pedestrian/Bicyclist Crash Analysis.

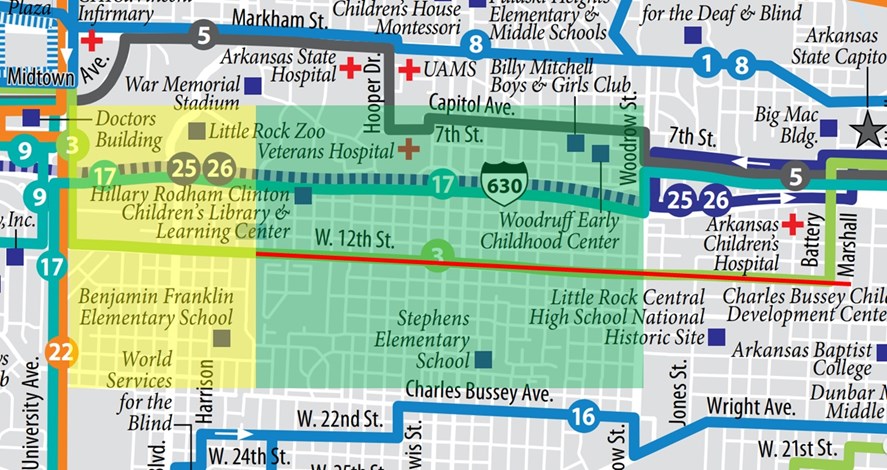

Another reason for this racial disparity may be the link between race and income. People with lower income more often walk and bike as transportation necessities. Many families in the Corridor cannot afford one or more cars (e.g. the average household income in one sampling unit of the Corridor is $13,396/year (Fig. 4) and the average annual cost of car ownership is $9,000/year). Accommodating bicycle and pedestrian mobility allows safe, independent movement within the Corridor and access to transit to move in and out of the Corridor (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Route 3 is the only Rock Region Metro route to serve the Corridor (Routes 17, 25, and 26 have no access on freeway). Making pedestrian and bicycle travel along 12th St. safer facilitates access to transit. Yellow box is Corridor not served by road diet, green box is Corridor served by road diet, and red line is road diet.

Road Diet Facilitates Corridor Revitalization

Road diets can spur economic development and can be an important part of revitalization of an area. This project was motivated by the desire for both Corridor revitalization and regional bike mobility.

Regional Importance

We have a small (but growing) number of bike commuters, in part, because we do not yet have a connected set of bike facilities that encourage ridership (Fig. 7). We know from the experiences in other communities and local polling data that we have a tremendous latent demand for the bicycle as a mode of transportation. An east-west connection has been particularly sought after because of a concentration of jobs in downtown Little Rock and a concentration of residences in west Little Rock. At the time the 12th St. road diet was implemented, it was the longest, most ambitious project to create on-street bike connectivity for bike commuters.

Figure 7. This present-day map of the proposed (dashed) and installed (solid) Master Bike Plan shows the importance of 12th St. (highlighted yellow) as an important east-west bike connector and that we still have work ahead to implement bicycle connectivity.

History

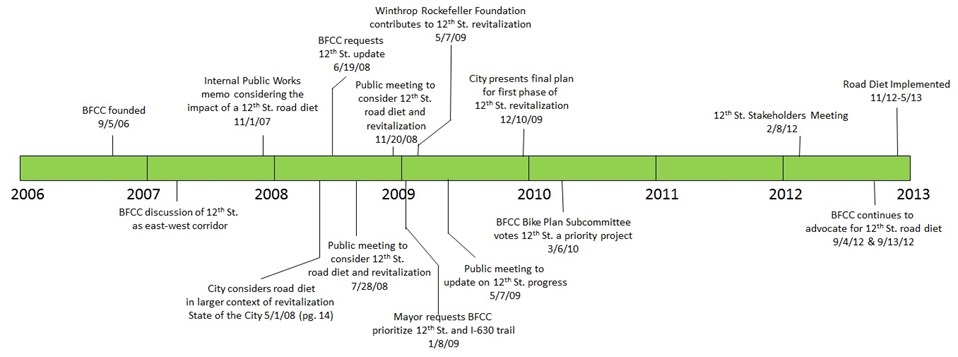

The 12th St. road diet has always been intertwined with on-going efforts to revitalize the Corridor. Soon after the Bicycle Friendly Community Committee (BFCC) was formed by the Mayor in 2006, it recognized the importance of a continuous east-west corridor (a facility still sought, Fig. 8). In 2007, the BFCC and the City identified 12th St. as an opportunity to create part of that connectivity through a road diet (Fig. 8). An internal Public Works document confirmed that a road diet was appropriate for some of 12th St., but traffic volumes were too high immediately east of University Ave. (Fig. 8). In 2013, Mayor Stodola discussed the road diet in a larger context of 12th St. revitalization in his State of the City Address (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. A timeline of the events leading to the 12th St. road diet implementation. A special thanks to BFCC Voting Member Ken Gould for compiling this history.

The City of Little Rock hired Crafton Tull Sparks Associates to advise and help develop a 12th Street Corridor Plan. The City held public meetings to elicit public opinion on the 12th St. road diet and revitalization on 7/28/08 and 11/20/08 (Fig. 8). In January 2009, Mayor Stodola requested the BFCC prioritize the 12th St. road diet and the I-630 trail in an effort to obtain economic stimulus package funding for the projects (Fig. 8). On May 7, 2009, the City held another public meeting to update the public on progress to date and on 12/10/09, the City presented its final plan for the first phase of 12th St. revitalization (Fig. 8).

There was not a lot of obvious movement on the project in 2010 and 2011. The 3/6/12 public Stakeholders Meeting was in part an effort to keep “momentum going”. In Fall 2012, the BFCC encouraged the City to be more specific regarding the timing installation of the 12th St. bike lanes. The 12th Street road diet was completed between November 2012 and May 2013 (Figs. 8 & 9).

Figure 9. 12th Street road resurfacing projects between November 2012 and May 2013. Blue circles represent road diets, purple circles kept four lane configuration.

Since the road diet was implemented, revitalization efforts continue on 12th St. The Little Rock Police Department opened the doors to their new 12th St. Station on 9/25/14. Part of the Corridor was awarded Metroplan Jump Start Initiative funding, a community-led process to revitalize the 12th St. Core.

Who Cares?

The 12th Street road diet is done. Why spend time considering how or why it was accomplished? While the 12th St. road diet did great things to increase age, race, and income equity in the 12th St. Corridor, promote continuing revitalization in the Corridor, and facilitate bicycle transportation in the City, these continue to be important goals in Little Rock as a whole. Understanding how a road diet can affect neighborhoods and our city-wide transportation system is important to motivating future improvements. Understanding the process through which the changes took place can help build a blueprint for future efforts.

So what can we learn from this process? These are my takeaways:

- Change can require both patience and persistence. The timeline shows that the 12th St. road diet took time, but it was a regular focus of the BFCC. Any future efforts should attempt to strike the right balance between patience and persistence.

- Change requires an ongoing dialog with City staff and elected officials. Especially when the Mayor first formed the BFCC, elected officials and City staff members were regular attendees. Because of this, BFCC discussions about 12th St. included these participants and awareness of the needs for 12th St. were raised. Future efforts can benefit from a sustained and constructive dialog with experts and decision-makers within the City.

- Change can be facilitated by considering the needs of others. The BFCC’s primary interest was to create a bicycle transportation corridor, but considerations of how a road diet could address the local needs of the 12th St. Corridor may have ultimately contributed to road diet implementation. Future efforts may be most successful when benefits beyond the bicycling community are considered and coalitions extending beyond the bicycling community are formed.

What are your takeaways from this process? Do you have any additional history of 12th St. to contribute? Contact us.